Riders: Doug Jansen, Dave Penney

Equipment: Dean Ti Cyclocross with 30mm treaded tires, 50/34t compact crank, 34t MTB cassette, and Independent Fabrications ‘cross bike with 28mm touring tires, 48/39t crank, 27t cassette.

Weather: Heavy overcast, looked like it could rain at any time, but it didn’t. Temps were cool, 60-70F. Negligible wind. Overnight rain left dirt tacky but not muddy.

So what is a “Randonnee?” Wikipedia says “A brevet or randonnée is an organised long-distance bicycle ride. Cyclists - who, in this discipline, may be referred to as randonneurs - follow a designated but unmarked route (usually 200km to 600km), passing through check-point controls, and must complete the course within specified time limits. These limits, while challenging, still allow the ride to be completed at a comfortable pace - there is no requirement to cycle at racing speeds or employ road bicycle racing strategies.” The D2R2 route was to include 70% non-paved surfaces.

Our ride started about 7:45am, 1 hour, 45 minutes later than the official 6am start time. We did not want to get up at 3am to make the official start time, and we were not going to have our passport cards stamped anyway. We had almost two hours to make up and risked missing food stops before closure. Our pace to start was a bit hard in hindsight. At first we thought there wasn’t going to be much dirt, but that soon changed. Before long we were climbing rocky one-lane roads, double tracks, and Jeep trails.

The views were fantastic almost everywhere we went. Zero traffic on many roads. Didn’t encounter any cows in the road, but we did chase chickens out of the way and saw a large gaggle of turkeys. There were many hill top vistas from open grazing land. But these vistas had to be earned.

We weren’t sure if we would make the first check point in time, so we stopped at the Charlemont General Store to refuel. We hadn’t yet caught up to anybody that left with the main pack shortly after 6am. The first stop wasn’t much further, but the second stop was about 67 miles into the ride, and the course meandered through remote country. When we reached the first stop, there must have been 20-30 riders still there. Most of them were doing the 65 mile route and started at 9am. We grabbed a bite and split.

The ride became a pattern: Climb 4-8mph for 15-30 minutes, rocket down

at 30-40+mph in a few minutes. Repeat often.

There just wasn’t much in between.

When we got to 25% grade

After the second rest stop, we thought we only had about 34 miles to go. Wrong! The ride was advertised as 100 or 106 miles depending where you looked. We now realized it was going to be 116 miles after looking at the last page of the cue sheets. I was beginning to feel trashed at this point, and we still had 50 miles to go! I got just a little grumpy, feeling the bonk coming on. I also became deeply suspicious that this ride would entail a lot more climbing than the claimed 10,200 feet. I did not wear my S725 for this ride, so I would have to check Topo later.

We had several more climbs between 2nd and 3rd rest stops, including 20% grade, 1000ft Patten Hill. This came late in ride, and I had no gas left in the tank. Starts as über steep pavement, then shortly becomes a sustained gravel grind. View from top was nice, but I was too delirious to fully appreciate it. Third and final rest stop was over the top of Patten Hill. A rider there with GPS said he already logged 4000 meters (13,100 feet) of climbing, and we still had 16 miles to go! Fortunately there were no more serious climbs, just “rollers” we were told. Some of those “rollers” took over 10 minutes to climb.

We rolled back in with 8 hours, 41

minutes riding time. This gives an

average speed for the 116.1 mile ride of 13.4 mph. Although we had no intentions of “racing”

this course, I expected a much, much faster time in planning. I got home two hours later than the worst

case time I told my wife. We were

completely cooked afterwards, myself probably more

cooked than after a hard-paced

Notes

on ride stats:

Cue

sheet said 180km (100 mile) ride with 10,200 feet of climbing. First off, 180km is about 112 miles. But then this doesn’t agree with the

finishing distance of 116.1 miles on the cue sheet either. These distance numbers should at least agree

with each other. I believe 116.1 miles

is quite close to truth, so the ride should be called 187km (116 miles). I measured 114.2 miles, and we made no wrong

turns, took no short cuts, and no doubling back. But I forgot to calibrate my cycle computer

for the large 30mm Cyclocross tires. The

computer was still set to 210cm for 23mm road racing tires. I measured the circumference of the 30mm

tires to be 212.3cm by performing a weighted roll-out. When correcting the measured distance by this

ratio, I get 115.5 miles, in close agreement with the final cue sheet finishing

distance.

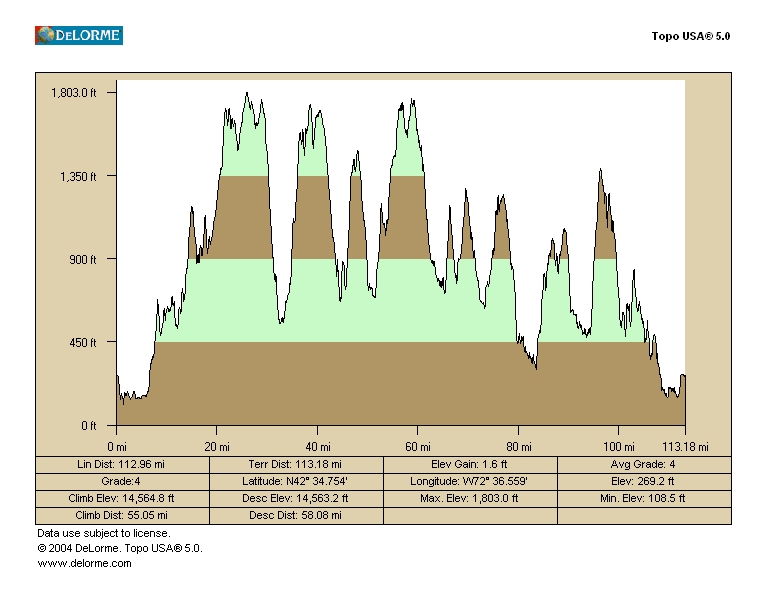

Now for elevation gain. The profile and

total climbing for a course can be found three difference ways, GPS, barometric

altimeter, and various topographic software applications. Each of these has weaknesses. Barometric altimeters, as found in HRMs and some GPS units, often do not count small rolling

changes. The air pressure must change a

minimum amount before a change is registered.

This is necessary as wind causes noisy pressure changes. You do not want to record this as elevation

fluctuations. So in Polar units, they

have 16 feet of hysteresis programmed into the

unit. If a measurement is recorded at 0

feet, then you drop 15 feet, then climb 30 feet (15ft above starting point),

the unit will not show an ascent accumulation even though you climbed 30

feet. Climb 16 feet or more from last

sample, it will register. Many small

rolling hills get under counted.

Atmospheric pressure changes can cause under or over measurement of

elevation gain. From high to low

pressure, over 2000ft elevation change can occur. When atmospheric pressure

is stable and large climbs are traversed (not a lot of small rollers), an HRM

altimeter can be pretty accurate.

GPSs are terrible at directly measuring elevation

changes. That is why some GPS units use

barometric altimeters instead of relying on elevation from satellite

position. GPS is highly accurate in

measuring where on the surface of Earth you are. The Z-axis is problematic. That is why you download a track file into a topo application to extract elevation data. This is most accurate way to find

profile. Using topo

app directly is not very accurate. Most topo apps simplify geographic features, approximating roads

with straight line segments. This cuts

across contour lines in software where road in reality follows the

contour. Thus when profiling a road

poorly mapped like this, an elevation change will be shown where none

exists. I use DeLorme

Topo

So

what did the ride entail? Cue sheet says

10,200 feet. The rider with a Garmin eTrex GPS presumably had

barometric data and was already at 4000 meters at the last check point. This is 13,100 feet. I don’t know if the rider rounded up or down

to a nice, even 4000 meters. Topo says 13,044 feet at last check point, spooky close to

the GPS measurement. Topo

gives 14,560 feet for the whole ride.

Truth is probably a little less than this, but likely over 14,000

feet. I do not know how the route

planners arrived at their elevation gain.

It might be simply adding up the net gains of significant climbs

only. The most accurate number I know

how to obtain would be to load a GPS track file into Topo. This removes the quantization errors in Topo’s linear approximation to curved roads. Does it really matter? Most would say no. The ride was friggin

hard. Don’t need any number mumbo jumbo

to explain why it hurt so badly.